It’s 4am, still half dark outside. Moyna Begum wakes up from the sound of water rushing from the tube well. Her first thought is how long that queue gets every morning. 10 families share one tube well and one hygiene facility. She rushes to the tube well with a bucket, to collect the water she will use for the rest of that day.

Moyna lives in an informal settlement in Gazipur, an industrial area near the capital Dhaka, in Bangladesh. She works in a garment factory, six days a week for 11-15 hours on average. She earns approximately USD 96 every month – the average monthly salary of garment workers in Bangladesh – and sometimes a bit more if she does overtime. That money vanishes instantly, in rent, utility bills and groceries. Health insurance, or saving for the future is a distant dream.

Women like Moyna are the backbone of Bangladesh’s ready-made garments industry, which is the second largest exporter of garments globally. The industry employs an estimated 4 million workers, most of whom migrate from across Bangladesh to work in the industry. Over 2,000 people migrate daily to Dhaka alone in search of better livelihood opportunities. Every day, long queues of prospective applicants at the gates of garment factories is a common sight.

Working in garment factories requires specific skills, though most people lack these when they first look for jobs. As a result, they often struggle to secure a job and if they do get one, it is low-skilled and low-paying.

To cope with the combination of low wages and high living costs, multiple families share one house – each family occupies one room with limited supply of gas, electricity and water. Spending on things such as proper sanitation practices, nutrition and healthcare fall far below.

Domestic abuse was the reason why Moyna left her village. “My husband used to torture me for dowry almost every day. He then left me, and married another woman. To get treatment for my injuries, I left for Gazipur, and decided to not return to that place ever again”, says Moyna.

“I started looking for a job in the garment factories here, but no one was taking me as I did not have any prior experience. So I kept looking.”

Moyna’s neighbours told her about a training centre operated nearby by BRAC’s one-stop service centre. She enrolled herself in a three months-course free of cost, on operating industrial sewing machines. Upon completion, she was referred for a job in one of the member factories of the centre.

Securing a job is only the first challenge, though.

The nature of work in garment factories is fraught with 11-15 hours, often in the same posture for the entire duration. Over time, workers often suffer from back pain and other complications, but opting for treatment requires time and money – two things the workers lack the most.

Women workers have double the challenge as when they first move, there is an overall lack of support system in the new city. The only family members they have with them are often their husbands and children. If they face domestic violence – which is common due to tensions arising from uncertainties and expenses of living in the city – the lack of a support system (such as family and other known people) means they don’t know where to seek legal help.

This challenge further intensifies during sudden shocks, such as illness of family members, pandemics, fire outbreaks, as they hardly get to save any money.

Combined solutions under one roof

Realising the multidimensionality of the challenges that garment workers face, BRAC introduced three one-stop service centres in 2017, in the heart of three key industrial areas – Savar, Tongi and Gazipur.

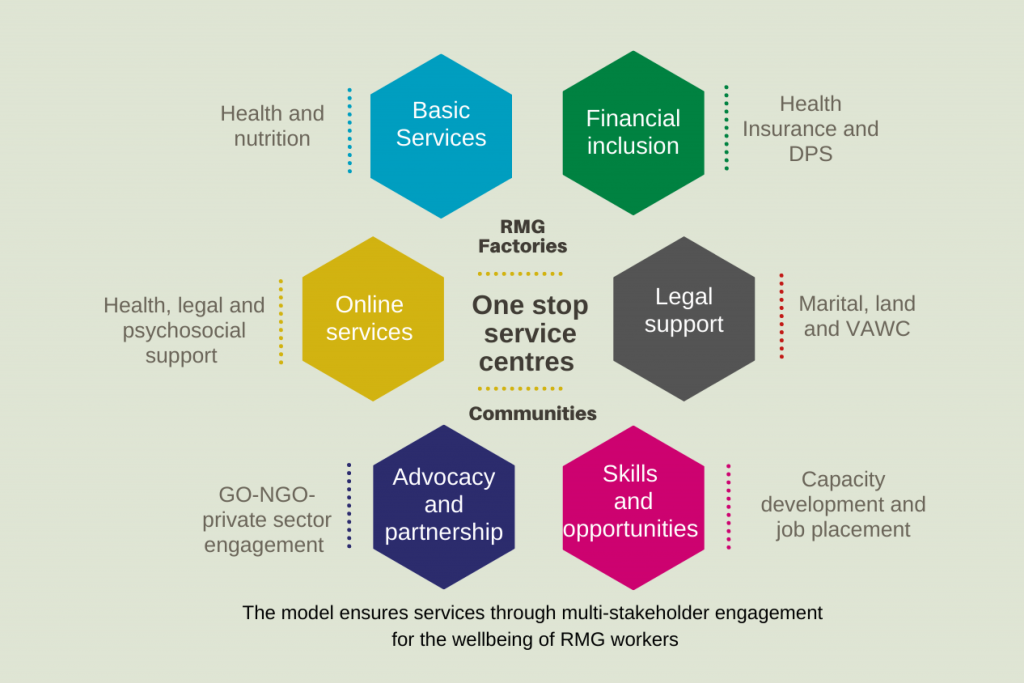

In partnership with 30 factories, Gazipur City Corporation and Pragati Life Insurance, these centres ensure different services through one platform, including skills training, job placement, quality healthcare, legal aid support, financial services, fixed deposit schemes, health insurance, and online counselling service on health, legal and psychosocial issues. All the services are free of cost for the workers of member factories. The centres are located within factories, and are open six days a week, in alignment with the workers’ schedules.

Watch: Empowering the Readymade Garments sector worker living in urban slums of Dhaka Project

Moyna, using the legal aid services from the centre at Gazipur, received the dower and maintenance benefits that her husband owed her, after they got divorced. She also started saving for her children’s education, using the fixed deposit scheme.

Over 50,000 workers like Moyna have availed at least one service from the centres. With a support system to seek legal support, plan for the future and access basic health care at their workplace and at their convenient times, garment workers are gradually improving their living standards – the dream that brought them to the city in the first place.

Illustration: One-stop service centre model

The centres are also benefiting the factory owners. Research shows that after the introduction of the centres, workers’ attentiveness and productivity improved, and absenteeism and dropout of workers reduced in member factories. It makes sense – more skilled workers in the entry level means effective supply chain management for the factories; workers being able to access basic health care and legal services means higher attendance and concentration in work; availability of health insurance and deposit schemes means higher loyalty and retention – all leading to effective recruitment and retention strategy for the management, as well as improved wellbeing for the workers.

Workers receiving health services at OSSC. Photo credit: Ahmad Ibne Salim, Urban Development Programme © BRAC, 2021

While the ready-made garments industry in Bangladesh has made significant progress in the last few decades, approaches to prioritise the wellbeing of its workers are still inadequate. However, solutions often lie close to challenges.

To bring sustainable solutions, the root causes of challenges must be identified, and tailored approaches need to be created.

In the case of garment workers in Bangladesh, ensuring access to basic services and rights, at their own convenience, is a step to secure the wellbeing of the workers. A life with dignity should not be a luxury.

BRAC Urban Development Programme aims to make cities inclusive, safe and sustainable through improving wellbeing, reducing multidimensional poverty and supporting people living in urban poverty to exercise their rights. It promotes community-led service integration, social enterprise approaches and public-private-community partnerships for pro-poor urban development.

Ahona Azad Choyti is a Communications Specialist, BRAC Communications.

Md Abdullah Al Zobair worked as Manager, knowledge management, innovation and communication, BRAC Urban Development Programme.